By Sara Mathov-Olszewicki for DMJ Zone

She does a full, fold wrap squeeze, thumb on the outside, drops her fist down to her waist, comes around in a circle like a piston on a train, practising smashing down and through. She lines up her fist to connect with the fleshy part of her palm directly on the board. “Squeeze your hand harder than you ever have in your life,” Wen-Do instructor Shai Keaney tells the woman.

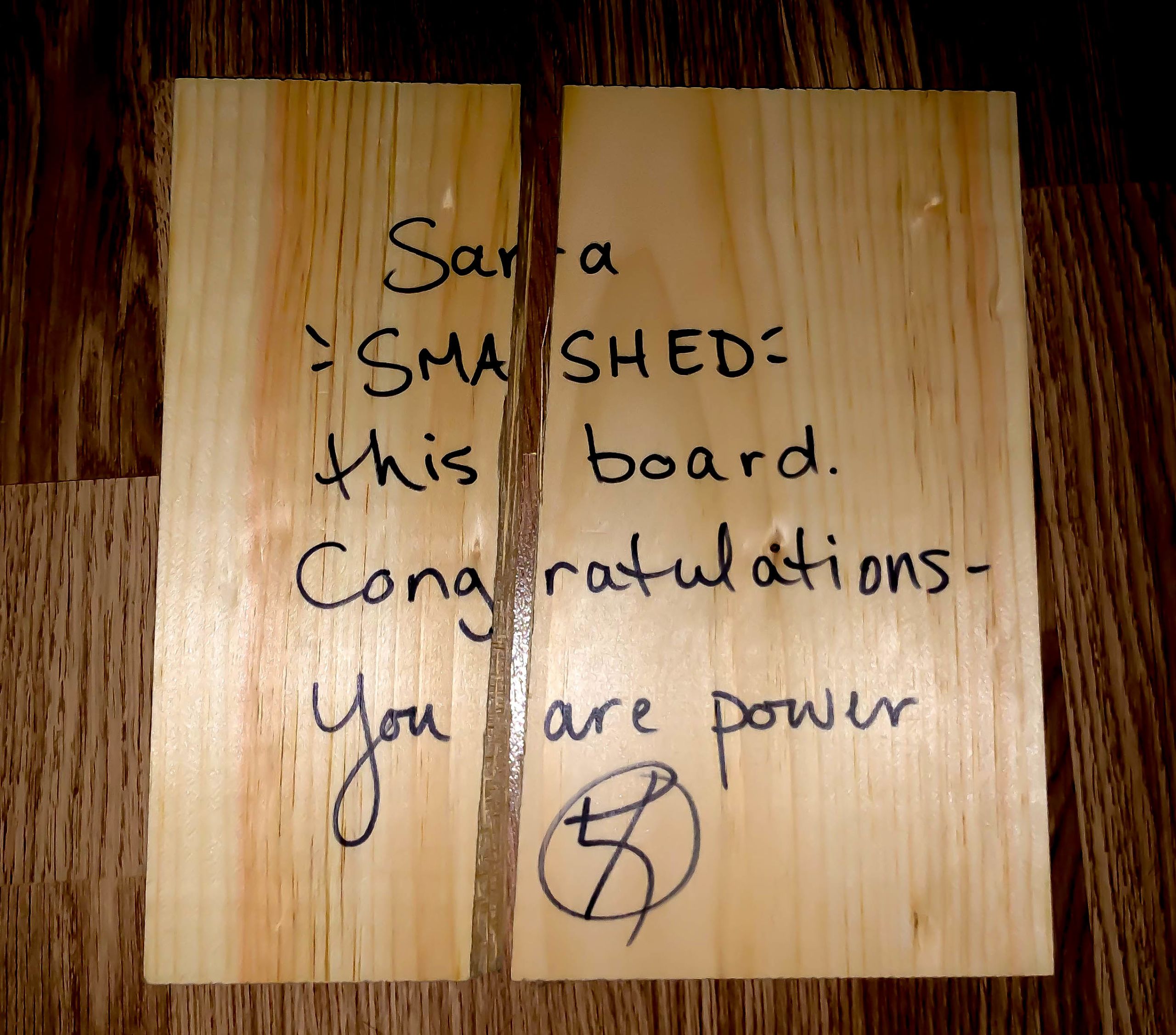

She takes a deep breath. We all watch in anticipation, is she really going to break a wooden board with her fist just like that? She rears back, releases a deep, fighting breath and cracks the board with a loud boom. Women around her applaud as she raises her hands to her face in shock.

“You only need half of this strength to break the nose of an attacker,” Keaney says. The woman takes the broken board signed with her name and promises to let people know that she smashed it herself.

This is how the women’s self-defence class at Laurier Brantford ended after two days of learning Wen-Do techniques. Keaney led the group through several Wen-Do moves to promote physical and mental strength.

Keaney says awareness and avoidance are the two goals of the course. It provides a space for women and non-binary people to talk about what it means to be afraid at night, says Keaney. “We don’t have enough spaces where we can talk about that in an empowered way,” she says.

Keaney started teaching Wen-Do after taking a class herself. She was already involved in gender-violence-based work and gender politics. Her friend was murdered in 2008. After finding Wen-Do, she says, “it was powerful, it was profound.”

She recalls her instructor explaining that it is never our fault if something happens to us. “I thought about my friend, and about the last reported hours of her life, and how I wondered if there was a way that she could avoid it, if there was a way she could have survived,” she says.

At the time, Keaney remembers the instructor saying that everyone has regrets in life, but it should never cost them their safety or well-being. “It hit home,” Keaney says. This helped her on her journey of healing. “Not that it’s ever going to be okay, what happened to her, but I harbour no shred of blame for her.”